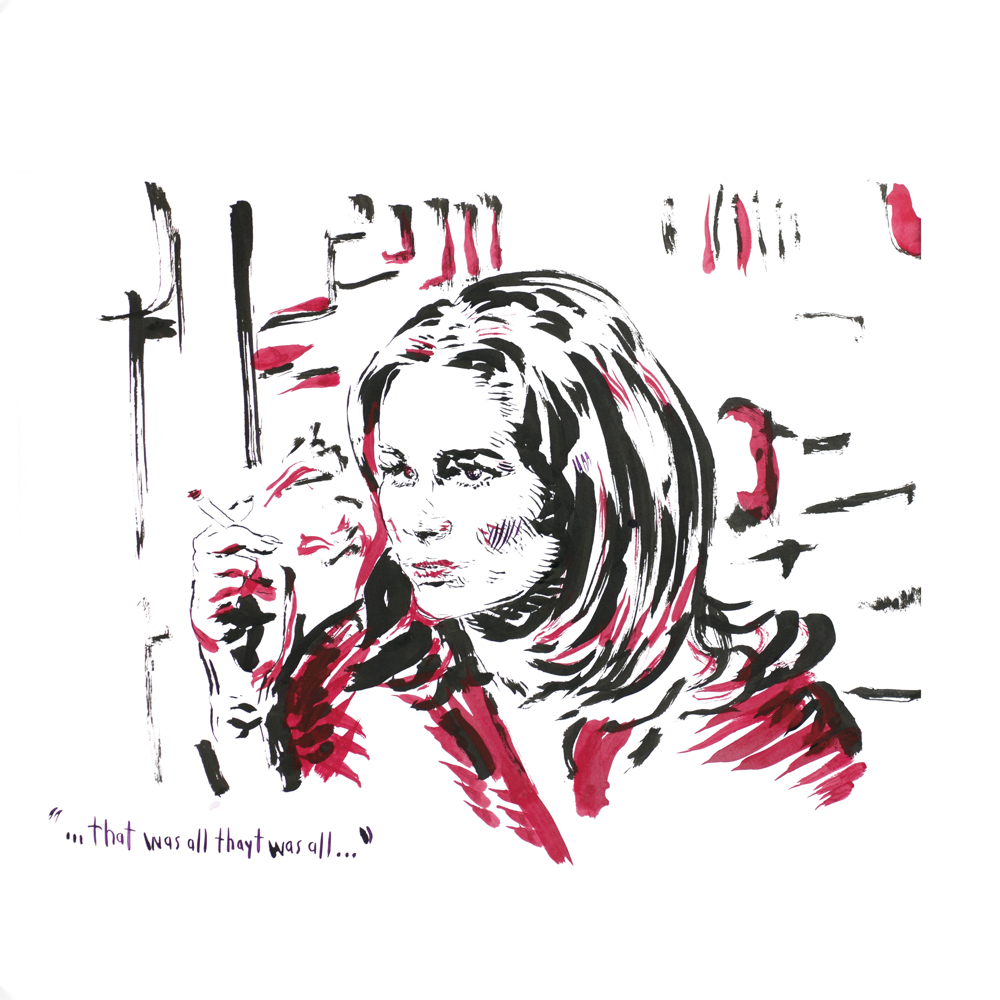

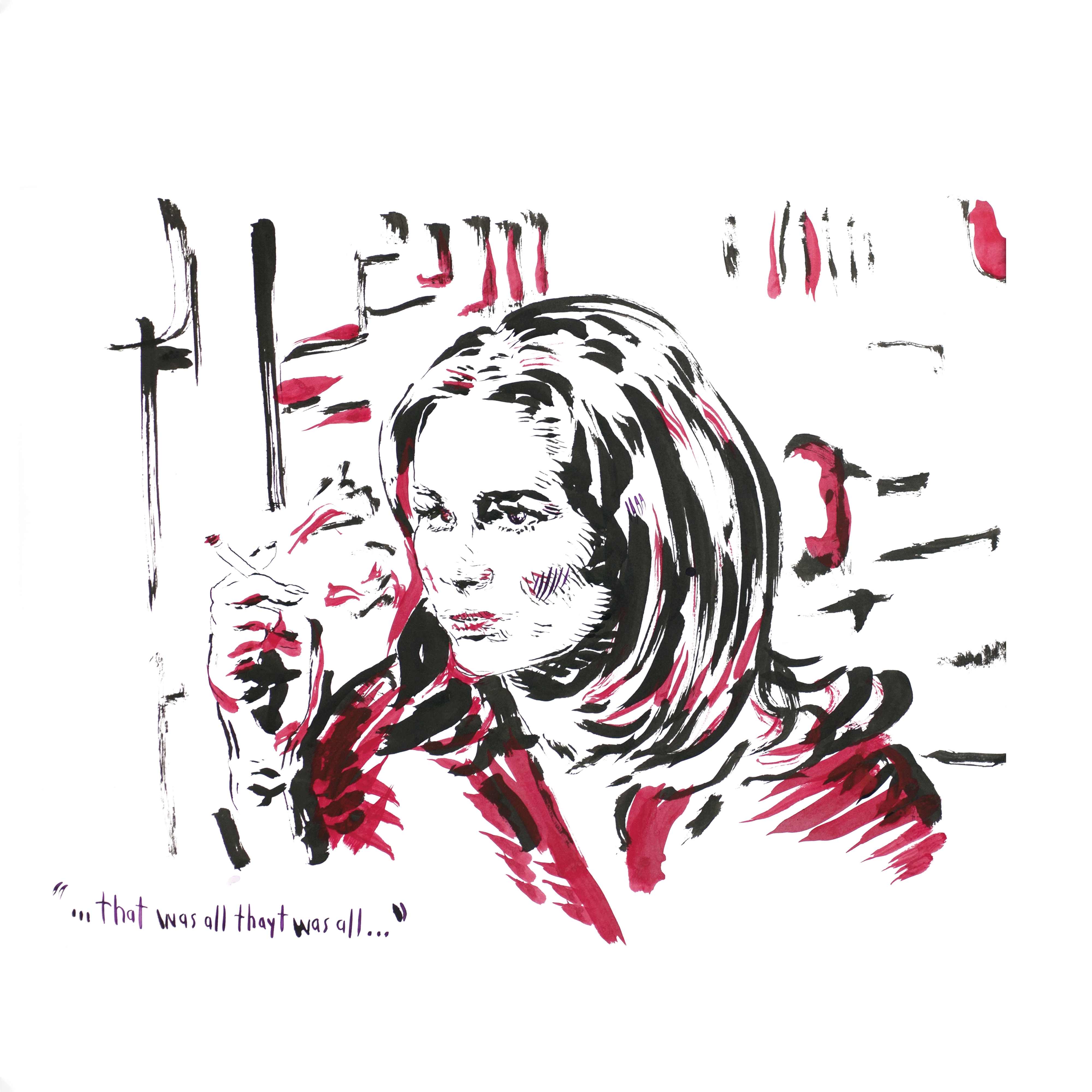

Dreaming of You (1971-1976) by Karen Black

(Anthology Recordings)

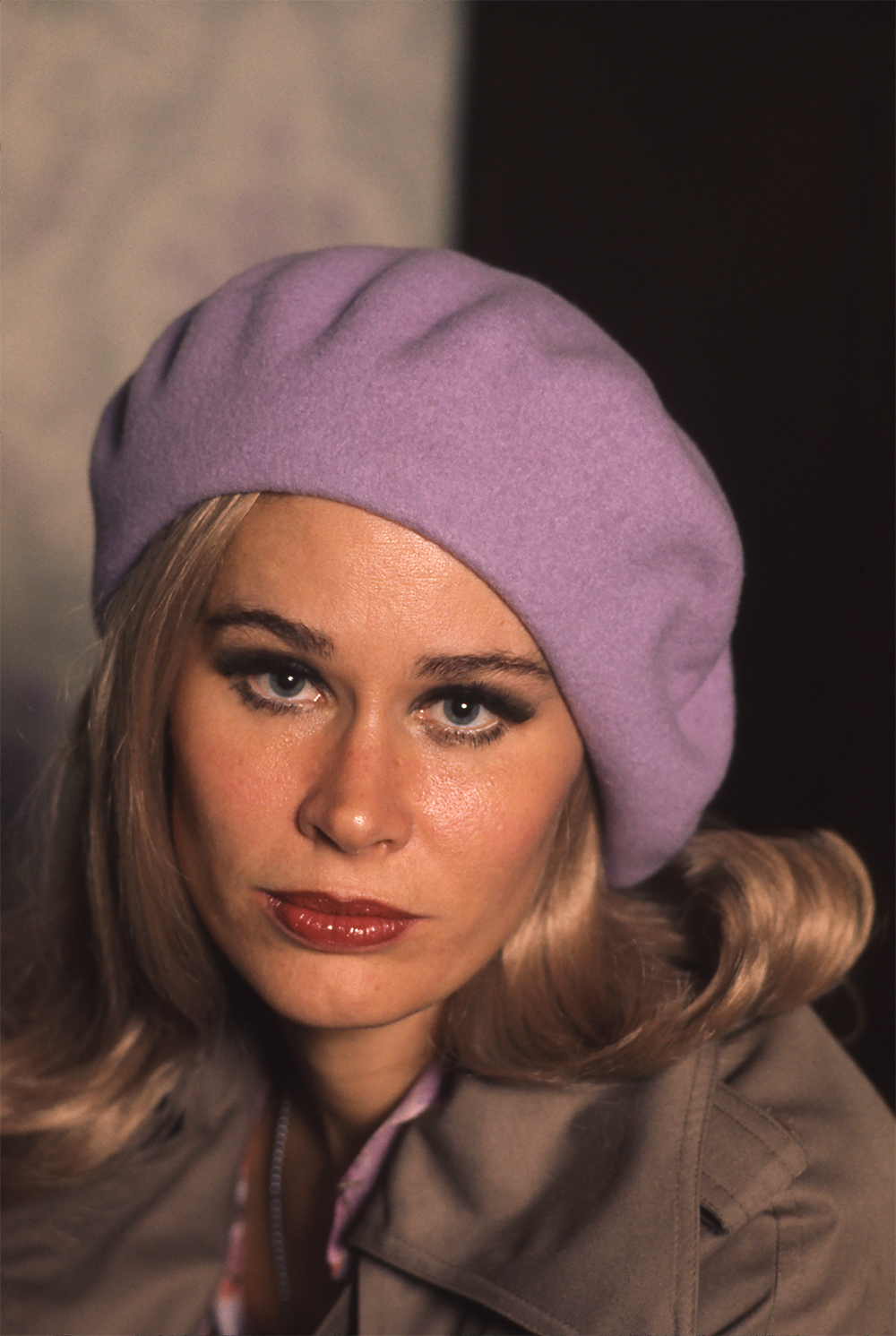

Karen Black was boundless. An actor, singer, screenwriter, poet, and unyielding creative spirit, she was a prominent figure in the American New Wave, portraying a host of tender and labyrinthine women on screen. Her ability to submerge herself in each role marked her as a skilled character actor, one that translated into a real and imperfect person, not a polished emblem of Hollywood. In her best-suited and most vulnerable performances, she sang.

Amid her meteoric rise, Black also wrote and recorded a host of original songs, many with two of the era’s most prestigious producers, Bones Howe and Elliot Mazer. Co-produced by Cass McCombs and meticulously restored from the original tapes (including six of Howe’s recordings), Karen Black’s Dreaming of You (1971-1976) gathers for the first time the best of her recordings: 15 tracks that are a holistic depiction of her dreamy, introspective and earnest musical identity.

Recalling the everywoman quality of Judy Collins and the quiet mystery of Billie Holiday, Black largely sings over simple acoustic guitar strumming, her voice a beacon amid tales of fantasy and heartache. Her range swings from fluttering highs to earthen lows, with a distinctiveness that evokes the enduring quality of early Asylum Records. When she wasn’t on set, she scrawled hundreds of poems and lyrics, and set them to acoustic guitar or piano. As with acting, for Black songwriting was a study in confession and in character. She often completed multiple takes of a song exploring that relationship, changing her tone, phrasing or cadence in each.

Black’s love of singing was a throughline in her acting career. Her breakthrough role in Five Easy Pieces (1970) was as small-town waitress and aspiring country singer Rayette, girlfriend of Jack Nicholson’s lost and philanderous rich kid—Bobby Dupea. During casting, director Bob Rafelson worried that Black’s insatiable mind was too complex for the simplicity he envisioned in Rayette. Instead, she elevated the character from unknowing victim to captivating moral compass, emanating light amid Dupea’s thunder of anomie. Her radiant singing, often improvised, became a calling card of a woman besmirched by devotion yet unyielding in goodness.

As Parm, she serenaded George Segal’s Jay with an original song in Born to Win (1971). In Cisco Pike (1972) she was Sue, the free-spirited love interest of Kris Kristofferson, in his film debut. She upstaged him in an impromptu duet of “I’d Rather Be Sorry,” before it became a hit in 1974. Robert Altman cast her as Connie White in his experimental opus Nashville (1975), a country star set on retaining her crown. She wrote the songs she performed in the film, including “Memphis,” “Rolling Stone,” and “I Don’t Know if I Found It in You.”

Though she never inhabited the traditional role of career musician, there was evidence of this desire throughout her films and public appearances. She performed her original songs on The Carol Burnett Show in March 1972 and again, five years later, on Dolly Parton’s short-lived variety show Dolly. A 1978 photo shows Black singing with Carly Simon onstage at Studio 54.

Black and Cass McCombs met in 2008 through a mutual friend, when he was in the midst of tracking his 2009 album Catacombs. “It was synchronistic because we’d just recorded ‘Dreams Come True Girl,’ and I’d left out the last verse for a yet-to-be-determined female vocalist,” he says. As a longtime fan of Black’s movies, McCombs immediately thought to enlist her, and she in turn agreed, without hesitation. “She was like that,” he adds. “She said yes to things.”

The pair became fast friends. They collaborated again on “Brighter!” from McCombs’ 2013 album Big Wheel and Others, and also wrote toward a solo album for Black. “She’d given me all of her poetry and I was trying to work them into some kind of meter that would work as songs,” McCombs says. They were able to record two of them before she died, “I Wish I Knew The Man I Thought You Were” and “Royal Jelly.”

After her death in 2013, evidence of Black’s prolificacy languished on quarter-inch reels in neglected boxes. McCombs and Black’s husband Stephen Eckelberry soon endeavored to revive them. For three years McCombs and Bay Area restoration engineer Tardon Feathered cleaned, transferred and reviewed the remains of Black’s musical legacy, working from tapes caked in mold and debris. What they found was an embarrassment of riches. “We went looking for a needle in a haystack, and ended up with a haystack of needles,” McCombs says.

Album opener “Sunshine of Our Days,” recorded by Howe, recalls his work with The Mamas and the Papas, with double-tracked vocals drenched in luminous reverb. “Dreaming of You,” a breezy love song also recorded by Howe, displays Black’s honeyed vocals and skill with phrasing. Her lyrics skitter in a gentle wind of emotion, and pour out breathful, convincingly optimistic and sunny. Black’s version of “Question” strips away the ornamentation of the original to more poignant effect, while “Babe Oh Babe” provides a rare glimpse of Black as frontwoman of an unknown country funk band.

“I Wish I Knew The Man I Thought You Were,” included here on a bonus 45, is a devastating account of the power dynamic between professor and student, based on Black’s experience at Northwestern University in the ‘60s. “I wish I knew the man that I thought you were / He’d tell me not to trust the man you are,” she sings unflinchingly over featherlight reverberations of acoustic guitar, bass, drums, and pedal steel, stirring a sense of distant memory and lingering hurt. B-side “Royal Jelly” reveals Black’s experiments with character, with somber and playful vocal takes layered over one another.

Among the trove of music Black left behind lingers mystery. Memories of her sessions have long faded. Tape boxes missing accompanying reels prompt further intrigue. What’s clear is the talent and ambition of a self-taught and self-made woman, making waves in a new era of Hollywood, and pushing beyond even those shifting boundaries. Her songs reveal a complete portrait of the musical identity she so often teased on screen, where confession and character form a poignant and singular bond. “Karen touched every person that she met immediately,” McCombs says. Through her recordings, that spirit lives on.