Stefan Wesołowski

The writer Max Sebald often pondered over the nature of human memory, specifically, how our thoughts and desires–and their results–overlap and change over time. In A Place in the Country, he writes of the significance of what see as “similarities, overlaps and coincidences.” Are they the “delusions” of the self and senses, or manifestations of “an order underlying the chaos of human relationships, [...] which lies beyond our comprehension?”

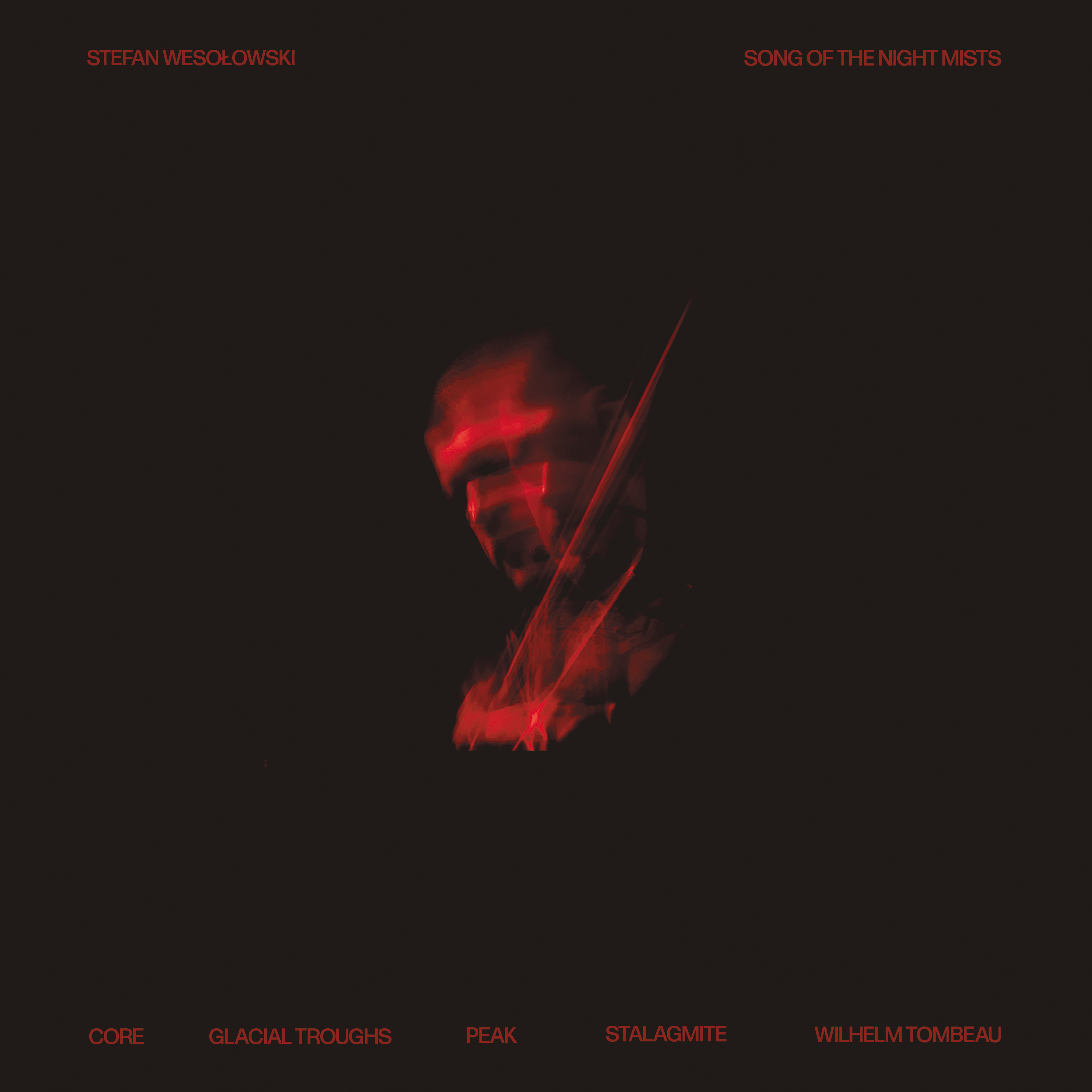

Song of the Night Mists, the new album by Polish experimental composer Stefan Wesołowski, often feels it draws on Sebald’s premise.

On a simpler plane, the one where the market dictates the neatly ordered information we consume, Song of the Night Mists can be described thus: recorded primarily by Stefan Wesołowski in Gdańsk–both in his studio and in Saint Nicholas' Basilica–the album incorporates acoustic instruments (piano, violin, double bass) and classic synthesizers such as the Roland Jupiter-8 and theSoviet Polivoks. A Roland SpaceEcho RE-150 tape delay was also pressed into service as an instrument. We also hear the basilica's organ and field recordings from the Tatra Mountains. Other musicians were Maja Miro, who played the flute parts on “Glacial Troughs” and brother Piotr Wesołowski, who played the organ on “Wilhelm Tombeau.” Sound engineer was Marcin Nenko, who was also on hand to record the basilica organ parts.The album was mixed in New York by Al Carlson (Oneohtrix Point Never, Jessica Pratt, Zola Jesus, Lady Gaga, and Liturgy) and Rafael Anton Irisarri handled the mastering.

Ostensibly,Song of the Night Mists is the last in a trilogy, following on from albums Liebestod (2013) and Rite of the End (2017). All three deal with existential matters such as love, death, decay and “an ultimate end;” apocalyptic and Promethean in spirit, and betraying very human conceits. The Sebaldian nature of the new record starts to make itself felt when Wesołowski talks of how he used sampling. One element is unexpected, that of sampling himself: “I go back to dozens of my own unused sketches and recordings, treating them as raw material to cut, slow down, reverse, and transform in every possible way.” Memory as sound, to be reemployed by the listener through their own imaginings.

Another set of samples made by Wesołowski play another role. These are field recordings, originally created for an audio illustration of the formation of the Tatra Mountains, and used in a film by sound designer Michał Fojcik. “You can hear cracking ice, streams, footsteps in the snow and the wind, and areal avalanche, recorded from the inside,” Wesołowski says. The “Tatra connection” on the album is also found in samples referencing composer Karol Szymanowski. The album’s title alludes to a poem about the mountains by Polish poet, Kazimierz Przerwa-Tetmajer.

Wesołowski’s Tatra recordings are “about a world without humans-about the fact that the world existed, was beautiful, and had meaning long before people arrived, and for the vast majority of its history, it was a place without us.” Wesołowski, using one iteration of the natural world, plays out in sound Sebald’s idea of another order, underlying the chaos of human relationships lying beyond human comprehension.

These feelings play themselves out on the five album tracks. Sonorous and rich, they illustrate tectonic shifts we have no control over. Wesołowski hints that the overall sound is a “meditation on the metaphysics of the non-human set against the spirituality that human presence has brought into it.” In that light, the opening number, “Core,” with its slow build, and crackling and straining sound effects, create an effect of the earth groaning into life in a creation myth. Once the piano part raps out a simple melody and modulated tonguing trumpet samples add to the overall atmosphere, the listener can certainly find a cue in the “spiritual,” or “human” side of the story. Human versus nature: from the strains and harmonic muscle stretches of the second number, “Glacial Troughs,” through to the powerful and filmic “Stalagmite”and heart-on-sleeve romance expressed in closer, “Wilhelm Tombeau,” we listeners are cast as Friedrich’s wanderer, looking out over a landscape that will appear only if we engage with it.

Formations of melody appear incrementally, almost appearing by chance–like hidden footings in the rock shelves to give us something to grasp onto. Rhythms are used sparsely: the prolonged percussive tap son “Glacial Troughs” are an anomaly and maybe there to give pace to the album to come; essentially to keep the listener strapped in. Elsewhere, percussion is used as an aid to mood, the two thudding, timpani-style passages on “Peak” there to offset the short, beautiful, kosmische passage that splits them.

Elements of the borderline religious spirit that drove German electronic music in the late 1960s and 1970s also find a place on Song of the Night Mists. The swells and recessions of the organ find their emotional climax on “Wilhelm Tombeau,” a track which summons up echoes of the “mountain magic” vistas created by Popol Vuh or Tangerine Dream, especially with the slightly atonal wobble of the Mellotron that counters it.

This is a dramatic album, but it does feel a strangely short, or curtailed listen on ending, evoking the feeling one gets when waking from a dream, and, for all its incipient grandeur, a track like “Stalagmite,”for instance, ends on a minor note. Wesołowski admits that Song of the Night Mists is born of the all too human process of temptation, doubt and recalibration–Sebaldian overlaps and coincidences forming something that must live another life, away from its creator. In Wesołowski’s words, the album is “a newborn foal must stand up and walk right after birth.” Now it is yours to ponder.